SIGNIFICANCE OF IGALA LITERARY CULTURE TO THE HISTORIOGRAPHY OF THE NIGER-BENUE CONFLUENCE AREA FROM 1800-1999

Musa Abdulkarim Itodo

Department of History and International Studies

Federal University Lokoja, Kogi State

E-Mail: musakarim162@gmail.Com

&

Binta Yakubu Sule

Department of History and International Studies

Federal University Lokoja, Kogi State

E-Mail: ybinta@yahoo.com

Abstract

The most dominant group in the Niger-Benue Confluence Area is the Igala. Being the most populous group, the influence of its literary culture on its neighbors cannot be overlooked. Thus, there is a great conurbation of acculturation between the Igala and its neighbors. This integration made Igala literary culture significant to the historiography of the peoples of Niger-Benue Confluence Area. Igala historiography relied largely on documentary sources particularly books written by western Europeans and some indigenous writers. However, the contextual features of Igala discourse literature such as folklores, poems, music and songs, proverbs, prose, among others that play significant roles in the reconstruction of Igala history have not received adequate scholarly attention. Consequently, the notion of documentary sources like books written on Igala history is often generalized, thus limiting the role of oral literary culture in the reconstruction of Igala history. The current study addresses the gap by focusing on some of the most fundamental contextual features of Igala oral literary culture which is very significant to the historiography of the Niger-Benue confluence area from 1800 to 1999. Adopting historical methodology, this study made use of both the primary and secondary approaches to acquire information. The primary sources were information obtained from oral interviews, supplemented by books, journal articles, newspapers, and internet materials like Facebook which constitute the secondary sources. Hence, the research discovered that the study confined its analysis to the significance of Igala literary culture source as folklores, poems, songs and music, proverbs and others in the reconstruction of the Igala history.

Introduction

This piece is an attempt to provide a brief account of the significance to historiography of the literary culture of Igala people in the Niger-Benue Confluence area. The literary culture of Igala people is deeply enshrined in their historical origin, political tradition and development, economic and social potentials; and Igala history, for long, has largely succumbed to documentary sources, particularly books written by the Europeans who were the earliest researchers on Igala history. Until the 1970s, foreigners such as G.M. Clifford (Igala Chiefdom, 1840s), Samuel Ajayi Crowther (1855), Sexton (1928; 1965), J.S. Boston (1968; 1969)and other non-indigenous researchers gave accounts on Igala history. Non-Igala researchers came under direct colonial influences and used the skills of writing acquired in colonial schools to compile and record Igala history. The most successful examples of this challenge to Igala history were Ade Obayemi, E.J. Alagoa and Samuel Ajaye (1970) among a few other examples. The striking indigenous work on Igala history was by Okwoli (1973), which came well before those of Ukwede (1976; 1987; 2003), Abdulkadir (1990), Miachi T. (1985; 2012), Yakubu (1995), Etu (1999), Omale (2000; 2004) Egbunu (2001; 2005), Edime (2006), Yusuf (2006), Ogba (2007), etc. These are examples of some of the documented works with specific thematic focus on Igala history by indigenous Igala authors from various disciplines and backgrounds. Most of these Igala historians paid much attention to the documentary sources and paid less attention to the reconstruction of Igala history through literary cultural sources such as folklore, proverbs, poetry, music, songs, artworks, ancient architectural structures and incantations, etc. The essence of this research is to examine and provoke the use of these sources in reconstructing the history of the Igala nation and its people. Through the literary sources, a historian gains handy knowledge of the sociopolitical, cultural, religious and economic views of Igala society.Igala people had, long before the Europeans’ intrusion in 1845 through River Niger and Benue into Igala kingdom, developed a literary culture.1 Although, this literary culture may not be known because there were no written records of it due to a lack of the knowledge of writing among the Igala, they came in the form of oral tradition. The introduction of the oral tradition account in the reconstruction of history devoid of documented evidence put the first task on a firm scholarly footing by Jan Vansina. This is found in his seminal works: Oral Tradition: A Study in Historical Methodology (published in French 1961, and in English 1965), and Oral Tradition as A Source of Reconstruction of People and Their Society History.2 African historians with varying degrees of success are increasingly coming to depend on ethnographic data for the reconstruction of African history, especially in the period before the coming of the Europeans. Jan Vansina defined ethnographic data as ‘’artefacts’’, custom or belief held by a group which testifies to their usage in the past.3 Okon Uya explained further in his book, African History: Some Problems in Methodology and Perspective that ethnographic data include music, songs, oaths, incantations, folklore, drumbeats, horn-blowing, proverbs, and pouring of libation, etc.4 Expatiating further, E.J. Alagoa, in his inaugural lecture note titled The Python Eye: The Past in the Living Present in 1979 emphasizes that oral tradition in the last few years gave Igala people the power to express themselves.5 This research paper carefully observes the use of literary sources in reconstructing Igala history in the Niger-Benue Confluence Area.

Conceptual Clarification

Niger-Benue Confluence Area

The Niger-Benue confluence area of Northcentral Nigeria today contains many different ethnic nationalities like the Igala, Idoma, Ebira, Bassa, Gbagyi, Nupe, Okun Yoruba, Eworo, Kankada etc. It is the area between the southern fringes of the old Northern Region and the Northern fringes of the old Western and Eastern Regions, and it is known as central Nigeria.6 This region has metamorphosed variously both in name and geographical expanse. Until 1999, it was popularly called Middle Belt and covered most of the areas that majority of the ethnic peripheries of the old Northern Region lived. Thereafter, the geographical scope expanded to include (southern Kaduna), Kogi, Kwara, Nassarawa, Niger, Plateau and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). The Niger-Benue Confluence Area was a melting pot of the peoples’ cultures and traditions. It is significant in literary cultures and several other aspects of human activities. The region is midway between two geographical zones, being a transition from the forest to the wide-open grassland vegetation. This gave it the advantage of being in both zones – forest in the South and open savannah in the North. These groups crisscrossed the region from all directions. It is rich in customs, culture, traditions and religious practices. It demonstrates that prior to 1800 the history of Igala and other ethnic groups in the Niger-Benue confluence area was enshrined in their oral literary culture devoid of dependency on documents to reconstruct the people’s history. According to Ahmed Rufai, the Sokoto jihad of 1804 to 1900 engendered alterations in the people’s literary culture as some were converted to Islam while majority of the people continued with their traditional practices. Following the imposition of colonial rule, Muslim converts were used as political agents and also used their Qur’anic understanding and the European ways of documenting the people’s history devoid of their literary culture which is more important in the reconstruction of the people’s history and Igala history is not exempted. The study therefore confines it analysis to the significance of Igala literary culture to the historiography of the Niger-Benue Confluence Area.7

Historiography

History writing, like every other discipline, has certain qualities which make it peculiar. History as a discipline is associated with a particular way of writing and thinking, with a particular point of view. In general, there are two aspects to every discipline: the perspective and the methods. The perspective is the way a particular discipline views or looks at things, which could be an angle of vision, cosmology (worldview), etc. The methods have to do with the manner, approach and technicalities employed by every discipline.

These two characteristics or factors make up the element of writing or thinking of any discipline. In history, it is called historiography (historical methods of writing). Definition of history centres on man and society. History is an evidence-based discipline. This means that nothing qualifies as history without evidence to support any argument. A historian depends on evidence to support any argument.8 The search for evidence is one of the most important activities of a historian in the field, archive, or library, etc. Evidence from history comes in one of three forms but, for the purpose of this paper, we shall be restricted to oral literary culture evidences. Evidence of history comes in oral form, saying or gossip, and eyewitness account from different people with different perspectives. The last and biggest category is the oral tradition. It is a very specific form of oral evidence; the bearer may not be an eyewitness and the information usually lasts for a very long time, because the information might have been converted to prose, poem, music and songs and ethnographic data like material culture.9 These are the various types of evidence gotten from things people make use of in everyday life like Nok culture sculptures, Igbo-Ukwu artworks such as knives, pottery, building, etc. They play a very big role in historical reconstruction. It is on the above premise that this paper attempts to provide a concise Igala literary culture and its significance to the historiography of the Igala people in the Niger-Benue confluence area.

Literary Culture

The term “literary cultures” can be defined as written texts with artistic value, including the traditional literary genres of poems, fiction and drama and it can also be referred to as the tradition of people that came in form of ethnographic data.10 According to Jan Vansina, ethnographic data are “artifacts, customs, beliefs held by a group which testify to their earlier usage of the past.” Okon Uya also noted that ethnographic data include proverbs, songs and music, drumbeat, horn blowing, incantations, oaths, poems,11 plays and so on as seen in the introductory part of this paper. Expatiating further, E.J. Alagoa also asserts that, in Africa, the most significant documents may come to the historian in the form of oral literature or tradition, substantial ethnographic practices and customs of communities, in the languages spoken by the people to express their feelings concerning the relevance of a consciousness of the past in the present in music and songs, proverbs and aphorisms, poems, incantations.12 The people of Igala, just like other Africans, preserve their history in literary culture for the next generation. In Igala literary culture we shall emphasize folklore, proverbs, incantations, poems, music, songs, as well as others. According to James Onalo in his work titled: Igala People and Their Culture, folklores (ohiaka or ohia-ula) are aptly described in the category of proverbs which are rendered with relish by the people.13 Folklores are told in the evening by moonlight. In the evening, the people sit in groups, teaching and telling folktales. Most of these folktales teach history, morality and wisdom to the younger ones. Telling folktales remains the most viable means of transmitting culture and history from generation to generation amongst the Igala people. Folklores are also called Ohiaka or Ohia-ula in Igala language.14

Igala Folklores

A popular Agwude folklore in Igala history as was aptly narrated by Rev. Fr. Michael Achile Umameh reveals that Agwude or Agwu-Ebo is a mythical gladiatorial combatant and wrestling maestro in Igala history.15 That Agwude Ebo is one of the most celebrated combatants of them all, a wrestler against spirits of the underworld, a strong and accomplished fighter. Umameh illustrates Agwude Ebo folktales as it was told to him and other children of his age by his grandfather, Chief Okpanachi Umameh, (Agwutiti) Achanya Achadu of Igalamela (nine Igala clans) in his hut (Atakpa) one evening in the dry season said that the moon hung in the sky above us like a ripened egili (a round, edible fruit that is yellow inside).16

“We sat around our grandfather like an arc of little stars around a giant Sun. Looking into his eyes for cues, monitoring his red-and-blue beaded wrists for the Story time gestures. Suddenly we heard all the Igala great folklores half-sung and half said,” he said.

He further said:

Ohiaka mi kwo kwakwakwakwa

Il’oji endu kiane n ilia n’oji Agwude, Agwu-ebo

The words of the above do not have equivalent in English but the closest is Once Upon a Time, which is used to commence traditional storytelling.

Agwude had a wife called Ijojo and a brother called Ocholi (Ocholi ogako ma domu uja kuja ki nagbada: (the man who was called into a fight to increase the intensity of the fight). Ocholi was a great flutist (afufele) and played the okpachina (the Great War flutes).17 He stirred Agwude to a fight and at the sound of his ufele (flute), a thousand leaves of lips burst into an anthem of war: Agude Alima gada! Agude Alima Gada Kpoloko!!

Agwude fought the nine best fighters of Igalamela and won. Literarily, it means nine Igala clans or a group of people consisting of the nine autochthonous clans in Igalaland. It is believed that, by about 1257, the first Igala clan had emerged and eventually the number rose to nine by mid-15th century.18 By 1470 AD, the Igalamela council became the highest political authority in Igalaland.19 Ufele or Okpachina was one of the instruments of war and it was what the Igala people of old used to keep their warriors on the alert or for any challenge, and to defend their territories against external aggressions. This is significant for a historian to reconstruct history of the Igala warrior.

Agude-Ebo also fought and defeated marine spirit in rivers Niger and Benue. That influenced the historical development of Igalaland which served as the corridor for the movement of people, ideas, trade and culture between the people of Igala kingdom and other areas of the lower Niger and beyond, right down to the Niger Delta region.20 This fostered diplomatic relations between Nembe Kingdom and Igala Kingdom. The folklore developed orally is more significant to a historian than the folklore recounted.

The Agwude folklore recounts the significance of Ufele (flute) in Igala history as one of the instruments of warfare and entertainment mostly used during Igala cultural festivals and also to spur Igala warriors to war and stand up for their right in the face of suppression, intimidation and injustice, and to defend their territorial integrity. It is indeed the reality that Igala oral history, like that of any other pre-colonial African society, was shrouded in myths and fables. Therefore, folklore and stories (ahika, Ohika and ohia-ula) remain critical means of transmitting culture and history from one generation of Igala people to the other. Folklore remains very significant to historians for the reconstruction of Igala history.

Below are the images of the masks of Agwude warrior, Ocholi Ogako the great flutist and his flute.

Agwude Mask

Choli Ogako Mask

Ufele(Flute)

Above pictures adopted from “Michael Achile Umameh facebook page as seen in the Attah Igala Palace museum Idah”21

Igala proverbs:

The Igala people over time have developed their history and preserved most of their proverbs. Many proverbs have been coined to suit different situations and circumstances in Igala history. According to Chinua Achebe, “proverbs are the palm oil with which yam is eaten”.22 African elders use proverbs when they want to drive home some words of caution or when they want to teach the younger ones some wisdom or history. The Igala people have identified proverbs as a means of teaching or exhibiting actions which show their commitment to Igala history. It was their firm grip of proverbs that gave them the confidence to face the world and speak where their words made impact. An Igala proverb says: Ene kima rewa ugbo komi kpo n la neke rewa ugbo k one kuna nwu wa n (if one does not remember where one was drenched in the rain, one will not remember where one was made to warm oneself before a fire). It was this consciousness that made men like Attah Ameh Oboni, Sarkin Adaji Om’Itodo Adaji and Abubakar Audu, Adu-oja Attah Igala etc.23 to use Igala proverbs in ways that made eternal impact on the people even up to the generations of Igala yet unborn. Attah Ameh Oboni once deployed this proverb “omi akwu kpai anyo che i emi, amaa umama chei abo Igala’’ (meaning: tears and disgrace are mine, but the regrets are Igala people’s) in Dekina in 1956 while he was about to commit suicide. This same proverb was quoted by Prince Abubakar Audu in 2003 when he lost his re-election to the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) and Alh. Ibrahim Idris due to the perceived conspiracy of Igala people against him. This is very significant to a historian who wants to reconstruct Igala political history and the conspiracy among the Igala people.24 Yakubu Adaji, the first Ejeh of Ankpa spoke this proverb: eju ogijo ma bi onu (Kings are born while the elders are yet alive). To his credit, that could be used to reconstruct Igala history. All the proverbs above are very good and significant to historians for reconstruction of Igala history.

Others like the popular African proverb of unity and togetherness recounted by Victor Alewo Adoji during his senatorial election campaign added to the body of Igala proverbs: enedu gwu nyiwn ali ochu (Everyone sees the moon from his home).25 What this proverb connotes is that in Igala literary culture, the Igala are a people with widespread and deep culture and tradition that breed some level of respect, morality and good conduct. The Igala people are fond of eating together, drinking together, farming together and meeting together at designated points to discuss issues of common interest. Igala are a people joined together by a common determination to exist profitably, harmoniously and productively. However, right under that determination, the very factor that keeps a people separated and ideologically divided readily flourishes and floats from this political culture that is evidently rooted in the psyche of identifying with perceived greatness based on the mood of self-preservation and self-seeking which envelop the minds of the Igala people.

The Igala pride themselves on being imbued with sagacity in the rendering of poetic speeches through proverbs or aphorisms, the key words of which they use to name their children. Hence, several indigenous names are couched in proverbs, idioms or other forms of poetic expressions, reminiscent of the realities or history of the child’s parents’ lives before the time of birth. Some proverbial names that are significant to a historian for historical reconstructions are:

Ejura, a female name derived from the proverb, Eju ura onwu ma aji adu ubie’ (it is in the presence of affluence that one prepares for possible future adversity).

Mame (Umameh), Ma m’ene Oka, ma m’ene oma (You can borrow corn, but you do not borrow children).26

Atuluku, which comes from the proverb: Atulu akwu n (one who sells or preserves seeds or seedlings will not die). The deeper or intended meaning of the proverb in Igala literary culture is that the name or the memory of a man blessed with children, grandchildren and great grandchildren will never die.

Odiba, a male name derived from the proverb, Udiba kwu k’afu k’ i m’ene alumeji (when a person lying at the edge of a bed – shared by three – dies, the person in the middle is exposed to cold or fear of death). This is very significant historically by the name given to a child in commemoration of the death of a brother or sister.

Another proverb that is negatively impactful in Igala history is enwu kajuwe majen kifufia (what the chicken does not eat, it scatters). This is anecdotal and its physical manifestation in Igala literary culture is perhaps the most pervasive instrument of self-destruction of the Igala nation which has been imbibed and modernized over the years. Some of these proverbs grant impetus to the selfish desire of Igala politicians to perpetually stay aloof even if it is to the detriment of established laws, procedures and practices of society. It is so bad that in the Igala nation that if given the option of choosing between ceding a prominent position to another ethnic group so as to either ensure optimum progress and continuing in a retrogressive fashion and staying faithful to the language and its land, the average Igala would boldly choose the latter.

Prior to the arrival of the Europeans in Igalaland, the Igala people had long developed a literary culture through incantation (ule). James Onalo, in his pioneering work titled “Igala people and their culture” aptly illustrated the role of incantation in the development of Igala literary culture. This was in the form of urging an idol and spirit beings to move against one’s spiritual enemies using ofo kpai ule, the law of retributive justice, which rewards the upright and punishes the evildoer. Ule comes and takes a delightful kola-nut (obi) in the expression: ule lewa gb’obi and is used by an embattled victim of injustice, calling on the ancestors to come to his/her rescue.27 Igala also use incantations to invoke the spirits of ancestors and to make supplication to them for possible intervention in the affairs of men. Incantation, which is quite significant to a historian, was also developed orally. Incantations can be recounted or chanted based on the glorious or miserable deed of the ancestors or of the past kings in Igala history.

The Igala also express themselves in their sociopolitical, religious and economic lives through music and songs. The significance of music and songs cannot be overemphasized. The music and songs recount glorious deeds of past kings, warfare, migratory history and other aspects of Igala history. There is no gainsaying that music and songs have been a part of Igala life before the coming of the Europeans. Most of these songs were comic, tragic and tragi-comic on wars (ogwu) internally and externally. The popular examples are the Igala-Bini War (ogwu ibini) of 1515-1516, and the Igala-Jukun War (Ogwu Apa), which is said to have taken place at the close of the 17th or the beginning of the 18th century; Bassa Uprising (ogwu Abacha); and Mahionu War (Ogwu Mahionu) of 1916 to 1917.28

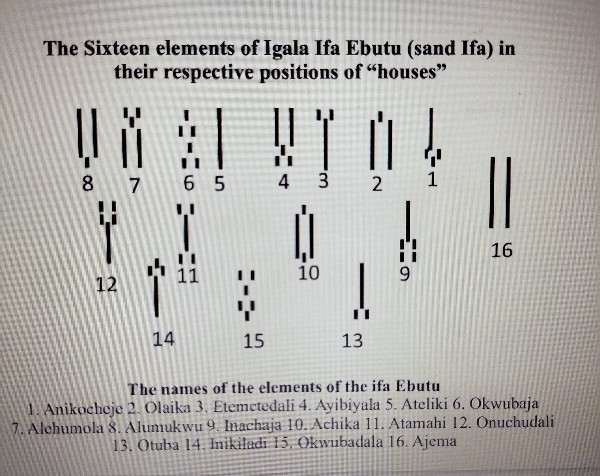

The songs and music also recount the history, life and times of Igala heroes: the likes of Atiyele, Attah Ayegba Om’Idoko, princes and princesses like Inikpi and Oma Odoko who fought and sacrificed their lives for the liberation of Igala kingdom. Songs and music talk about Igala deities that had been part of culture and traditions, and are also used as a form of entertainment during Igala cultural festivals. In this sphere, Winifred E. Akoda indicated that the historical significance of music and songs could be analyzed in the work of two famous and prominent Nigerian historians: Okon E. Uya and Samori Biobaku.29 These two prominent historians noted that “In songs, we find more passages of historical values.” Okon E. Uya also accepted the belief that music and songs are most important ethnographic data for historical reconstruction.30 Therefore, Igala literary culture was developed through music and songs whose sources were in oral context that could teach or educate Igala people of their culture and tradition. It should also be noted that the earliest attempt of Igala people to express themselves in writing was through ebutu ifa (writing of 16 elements or symbols on sand) that came in the form of hieroglyphic writings. Ifa is an enigmatic, spiritual authority that foretells the future and, in the process, discloses hidden information about human beings, and beams its searchlight both on physical and non-physical realms.

Above picture adopted from Ayegba A.A. Education and Research Unit, United Igala Kingdom, Idah, Kogi State. Sept, 2020.

The secrets of Ifa are known only to the holder of the highest enigmatic spiritual authority which is the priest of the land.31With the coming of European missionaries to Igalaland in 1810 and European explorers in 1900, Samuel Ajayi Crowder who arrived in Idah, the cultural and political headquarters of Igala Kingdom in 1812-1814 and 1902 actually made several attempts to translate and record Igala’s 16 elements of ifa vocabulary and made other publications on Igala Christian literatures.24 And, prior to the end of the twentieth century, the Igala themselves became conscious of developing and spreading their literature. This came with publications like “Mu-Igala” or the way of Muu, published in 1947 by Wassen Henry “Ibele’’; “An Igala Chant”, published in the year 1954 by Maiyanga, Alex A.I. Others are “Igala Expression and Historical Landmarks”, published in 1999 by Yusufu Etu; “Fundamentals of Theology and the Studies of Igala Language” published in 2000 by Gideon Sunday. “Okakachi Igala” (Igala Trumpet) poem published in 2004 by Friday Enejo Ikani; “Ukoche Igala: Arone Arone Mela” (9 stages in Igala primer), published in 2006 by Abbah, Ruth L.; and “Oral Poetry and Cinematic Transportation: Inter-Rotating Two Igala Folk Films”, published in 2009 by Aduku Armstrong Idachaba, were other publications. These publications till date encourage many young Igala sons and daughters to study and possess literary qualities that enable them to express themselves and know Igala history through this medium. Some did so in poetry like Ohiemi Gabriel who is a bard that worked on a love poem in Igala, published in 2017; and others did so in ballads, music, songs, and proverbs – like Isiaka Abubakar Easy, who worked on poetry, drama and prose of the Attah Ameh Oboni the Great. The poem tells of the experience of Attah Ameh Oboni (King of Igala Kingdom) at a meeting organized in Kaduna by the then colonial masters and emirs of the Hausa Kingdom. It was published on December 26, 1999: Igala: A Nation Now Torn Apart (a poem, Vol.1), he posit that:

A Nation Now Torn Apart

Oh, Igala, Igala, Igala!

How many times have I called thy name?

Who has bewitched You this bad?

Beneficiaries of Inikpi life-sacrifice, what has

Happened to you all? Where are the descendants

Of your ancestral brave men and women who dared

Powers until 1956? Did I say 1956? Yes, 1956!

A year of betrayal, and the man died! And his betrayal

Has come again. He has come with divisions.

But who planted these seeds of many colors in your farm?

Seeds of discords, seeds of defeat oh, Igala nation, why art

Thou falling before your subordinates? Why have your inferiors

Taken over birthright as the superior?

Why have they chosen money over your good name?

They now boldly bear arms against themselves, shedding the

Bloods of one another, even as they count fallen heads one by

One as they slaughter themselves

And this bloods dot your land oh Igala nation!

Today, the head is no longer connected to the body

Falcon indeed, can no longer hear the falconer

The chicks are now deaf to the chuckles of the mother hen!

But they hear the whispers of the kites and the hawks

A lion has begotten a rat, and the angers of the people

Cannot be counted! Oh, Igala, a tribe and a nation

Now torn apart, you are!

But, again, I ask, for how long would this be?

Let the gods belch now for we are tired.32

Poetry, which is more symbolic to historian, was also developed orally. Here, the bard chronicles the glorious deeds of past kings, (Attah Ayegba Om’Idoko and Attah Ameh Oboni). Attah Ayegba Om’Idoko, for the love of Igala Kingdom and the unity of his subjects he sacrificed his daughter Inikpi Om’Ufedo Baba to win a war for his people and the poem captured unity, love, warfare, sacrifices, conspiracy, declined values and traditions and other components of Igala history in a rhythmic and musical singing.

The poem particularly reveals the glorious deed and conspiracy against Attah Ameh Oboni, who ruled from 1946 to 1956, and the mention of his name today elicits a sense of awe, fear and respect. Tributes are paid to him not just for his avowed commitment to the unapologetic preservation of Igala cultures and traditions but also for his prophetic tongue and myriads of miraculous feats that are captured in poems, songs and many others. For instance, according to Yesufu Etu, in January, 1956, when Queen Elizabeth visited the Northern House of Chiefs and was shaking hands with all the northern kings assembled in the House, “of all the chiefs (present), it was Attah Ameh Oboni alone who refused to stretch out his hands to shake the Queen of England, a rite the other chiefs were apparently too eager to perform.33 His refusal were borne out of Igala customs and traditions; the Atta-Igala does not shake hands with anybody and it is inconceivable that Attah should shake hands with a woman.” This clash of cultures made the Lieutenant-Governor who did not understand the customary taboo constraining the Attah from having a handshake with Queen Elizabeth…the colonial administrators in the country never fully forgave Attah Ameh Oboni for this showdown on the Queen. Just after the above saga, the great moment to define Igala subservience arrived.34 The Igalas’ image (the Atta’s image at that time) began to be tainted with orchestrated opprobrium and predetermined scandal (that Attah Ameh Oboni sacrifices human beings to his deities) emanating from the perceived actions of the Attah Ameh Oboni. Some of the enemies at home (among the Igala people) accepted the vile accusations levelled against Attah and the accusations were allowed to thrive unabated while the reputation of his majesty dwindled and made him susceptible to assaults, especially from the colonial masters and their northern collaborators.35 The strategy was to whip up sentiments, defame the Attah’s name, disillusion his subjects and encourage them to be disrespectful to the Attah to level unfounded accusations against the Attah with a view to driving him into exile or igniting an insurrection that will form a basis that the subjects will rise against their Attah. In addition to this account, because of the purported accusations laid against him, he left Idah the political and cultural headquarters of Igala people for Dekina, in the present Dekina Local Government Area of Kogi State, where he was reported to have said that “Igala was the genesis of his ordeal (conspirators), there will be disunity among Igala people; that the Igala will continue to go against themselves and the land – and that we are witnessing today as Igala youths are taking up arms against themselves and shedding blood of their brothers on the altar of political thugs and the dichotomy of Ankpa, Dekina and Idah.36

Aside employing poetry to reconstruct Igala history, Igala music provides an efficacious spring for reconstructing Igala history. Igala music and songs usually communicate or express the people’s cultures and traditions. They are melodious and poetic in nature, and let on (about) not only the literary dexterity of the bard, but also his or her knowledge of the people’s historic events.

The Igala also express themselves in their religious and social lives through songs and music. There is no contradiction that songs and music have been an essential part of Igala culture and traditions from the remote past. Most of the music and songs were war (iya or Eli Ogwu), comic, tragic (iya-oye) on important personalities in Igala Society, love (eli or iya ufedo), and about Igala deities (Iya-ebo) and for general entertainment purposes.

The development and growth of Igala literate culture could be said to have commenced between 1800 and 1980. Men and women like Iye-Omakpelu, Ichakuba, Yahaya Ugwolu in Ankpa, Yahaya Ogbogodo, Paul Odih (Enegbani Idah), Alami Owi Aduku-Obia, Ilabija Oni Ogbaje, Titi Oyege, Joseph Abuh (also known as Joseph Alalor) were all great singers and poets of Igala kingdom of the era. It was a common saying that “Wherever any Igala traditional plays were to be staged, these musicians and folklorists were invited to sing because the nature of Igala music is literarily poetic in close contact with their language. Music is an essential part of Igala oral literature and tradition and this is used to teach their art, organize the plays according to the tradition of the elders.” Odih Daniel Nuhu used one of these people’s songs (of Iye-oma Kpelu’s) to write an Igala poem about glorious Ane Ayegba (Igalaland) published on Facebook, 2nd August, 2009. To Igala people, the poem represents a glorious Igala nation.

Glorious Ane Ayegba

Oh! My glorious Ane Ayegba, Igala Kingdom-O

There’s full of milk and honey flowing in Ayegba land

Glorious Igala kingdom-O

Oh! If you bespeak for etiquette and knowledge,

Go to Ane Ayegba where they super bound

Glorious Ane Ayegba- O ally, as soon as you set

Foot there you won’t desire to go back, noble women

Are abundant in Ayegba land vibrant, intelligent young

Men are to be found all corners of the land

Oh! My glorious Igala Kingdom, Ane Ayegba Oh if you

Craving for good life go to Ane Igala oh, glorious

Ane Ayegba oh!37

The above poem has revealed a lot about Ane Ayegba (Ane Igala), prominently known as Igala nation. Its characteristic as a land flowing with milk and honey corresponds with the Holy Bible that preaches about the promised land, a nation that is politically and economically attainable in the sense that its strategic location on a fertile Niger-Benue Confluence Area makes it viable for a bountiful harvest of economic crops, food crops and solid minerals. Different kinds of fruits and tuber crops are found in abundance. The Igala nation’s strategic location on the coastline of Rivers Niger and Benue creates access to sufficient seafood for the people and, therefore, validates the description of a land flowing with milk and honey. The poem views Igala nation from political stability and economic vantage points.

The poem also makes one to be abreast with excellent moral values and impact of Christian missionaries and Islamic education on the people of Igalaland. The educational achievement of the Igala people was as a result of the early contact with Europeans and itinerant Hausa Islamic scholars basically from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Therefore, the statement, “If you seek etiquette and knowledge, go to Ane Ayegba (Igala Nation) where they super abound”. It is noteworthy that Igala Nation was one of the first areas in the Niger-Benue Confluence region to embrace European and Islamic culture and education. For example, the Europeans arrived in Igalaland in 1857 and began Christian evangelization.38 They built churches and established schools in the metropolis in the 19th century.39 According to P.E. Okwoli, the Catholic Mission played a prominent role in the establishment of primary and post-primary schools in Igalaland. Like other missionary bodies, the aims of establishing schools were to fight ignorance, disease and to win souls to God.40 To trace the Catholic schools in Igalaland, we are to discuss the era of Bishop Shanahan’s stay in Dekina in the present Dekina Local Government Area of Kogi State. He established schools and churches and brought teachers to Dekina to teach in the schools he established in 1903 or 1904. He established primary and post-primary schools which were later placed under English priests. There, Igala Catholic teachers were trained. These include St. Frances College, which is now a secondary school. Igala boys also attended Alaide Secondary School near Oturkpo. The coming of the Canadian priests marked the establishment of Anyingba Teacher Training College (T.T.C.) in 1957, St. Peter’s College Idah in 1963; St. Clements College Akpanya in 1964 and St. Charles’ College Ankpa in 1967. The Igala pioneers that benefited from Catholic missionary schools are Mr. Gabriel Obaje who got his early primary education in 1926 at St. Francis Primary School, Mr. J. Aduku who was trained in St. Francis College Oturkpo and worked as a pioneer teacher in Ibaji and Mr. P. Achor who was also trained in St. Francis College in Oturkpo, and many others.41

It is also worthy of note that, the good moral values and educational attainment of the Igala people were a result of the early contact with Hausa/Fulani Islamic scholars. According to Adeniyi, many factors were responsible for the rapid spread of Islam and the establishment of Qur’anic schools in Igalaland. Some of these include trade and commerce, also the glorious activities of Ayegba Om’Idoko, the famous Attah Igala, the Fulani jihad and the immigrant Hausa Muslims. It should be noted that Ayegba Om’idoko’s reign witnessed a conflict with the Jukun.42 As Ayegba was faced with imminent defeat, he sought the assistance of Islamic preachers from Kano, who told him to sacrifice his dearest and most beautiful daughter Inikpi to avert the disaster ahead. After Inikpi had been buried alive to save the Igala kingdom, the Islamic preachers prepared a strong medicine that they cast into Inachalo river near the possible Jukun’s route to Idah.43 The result was the miraculous rise of fishes. And when the Jukuns ate them they were greatly weakened and poisoned. Ayegba eventually defeated the Jukuns in battle. Attah Ayegba thus gave official recognition to the religion of Islam, but he never converted to Islam before his death.44

Later on, other Muslims came from the same Babeji in Kano and were settled at Angwa Jammah in Idah. Attah rewarded them for their services by recognizing them as Islamic priests and they acted as scribes at the Attah’s court to influence people to accept Islam as the natural religion. The people started studying the Qu’ran and other Islamic practices and established Qu’ranic schools in many cities and villages in Igalaland where the children learnt Islamic sciences, art and literature.45

Both Christian missionaries and Islamic schools helped train many Igala sons and daughters as teachers who assisted the colonial government in Igalaland to run schools in interior villages. Similarly, the presence of Christian missionaries and Islamic scholars exerted influence on the religious, moral and educational life of the Igala people. Therefore, the amicable and high moral standards of the Igala people as pictured in the poem. The poem also portrayed the hospitable and welcoming nature of Igala people, which makes visitors feel reluctant to go back to where they came from. The poem went further to praise enthusiastically the beauty and the green nature of Igala nation which guarantees visitors peace and tranquility in Igalaland. With regard to Odih Daniel Nuhu’s poem (Glorious Ane Ayegba) . . . the song by Iye Oma Kpelu, which this poem was composed from, gives a historian the social and economic perspectives of Igala’s past and is one of the examples of how Igala songs and music could assist historical reconstruction. Simply put, Igala music and songs played prominent role in cloning the past Igala society apart from being used to entertain.

Aside from the folklore, poems and songs analyzed above, from 1970 onward, there was a general spontaneous increase in the rise of Igala literature expressed in poetry, prose and drama. Some of these writers wrote in English and Igala languages. They include Aduku Armstrong Idachaba Solomon Akobe, Etu Yusuf, Alex A. Maiyanga, Ikani Friday Eneojo, Abbah Ruth I., Isiaka Abubakar, Rev. Fr. Onoja Akpa, and Rev. Fr. Michael Achile Umameh, amongst others. In the case of Michael Achile Umameh, an indigene of Idah, his works are in various topics such as folklore Agwude, the Great Wrestler published in 2013, basically educating younger readers. He writes poems, fiction and non-fiction. His recent poetic works: Memoir of Reluctant Prodigal (2006) and The Mills of the God and Other Rented Tears (2011) serve as a veritable guide for a researcher on Igala history because they illustrate important historical information like Ogugu geographical location and their cultural values in Igala kingdom. John Idakwo wrote in Igala language, An Igala English Lexicon (otakada ofe ukola Igala alu enefu) first edition, published in 2015. Idakwo has also written fiction and non-fiction. His non-fictional works serve as a proper guide for research into Igala history. It actually highlights such important historical information like the Igala days of the week, political, economic and social activities carried out during these days as well as their significance to the history of the Igala people.

Historically, there are four days in a week in the Igala calendar (Ojo aja efu Igala). Idakwoji, in his work, noted that the Igala people had four days in a week, namely, Ojo Eke, Ojo Ede, Ojo Afo and Ojo Ukwo.46 Most of the big markets in Igalaland like Ajah Ejule in Ofu L.G.A., Ajah Abocho and Ajah Alijobu-Anyigba in Dekina L.G.A. and Afo-Gamgam in Ankpa, Ankpa L.G.A. all in Kogi State were named after the four days in a week of the Igala Calendar. The names of the traditional four days of the week in Igalaland exist among the Igbo too. This also proves historically that Igala and the Igbo share common linguistic, cultural, political and economic affinities. Igala do not tie significance of the days of the week to ‘big market’ only; they also give the names of the four days in a week to their female children as a historical reference to the days of the Igala week they were born on. For instance, ‘Ede’ name in Igala tradition is considered the most fruitful day of the Igala week, the day on which legitimate business is believed to thrive best and particularly the day that good things happen.47 This explains why most people choose the ‘Ede’ day not only to do business but also to hold or mark important traditional and cultural events in Igala kingdom. According to Edimeh, on the seventh day of the beginning of the Egwu (masquerade) festival, that is on ‘Ukwo’ day, the Attah Igala accompanied by the Ateebo (priests) and senior eunuchs (am’akpino) would lead an uncounted number of horses in a procession from the Attah’s palace to Okete Ekwe, where the Attah would offer a goat and kola-nuts and make invocations to the ancestors of Igalaland. This ceremony is to commemorate the death and heroic sacrifice of Inikpi Om’Ayegba, Oma Odoko and Obaka the friend of Attah Igala for the safety of Igalaland during the Benin and Igala war and the Igala-Jukun war.48

Similarly, Aduojo A. Ayegba examines the weaving of raffia grass (ichala) for the roofing of the traditional Igala houses during the pre-colonial period. Ayegba also proves himself as one of the greatest Igala poets in one of his works “Odo-ogo” meaning security tower. His poem refers to the various Igala governing structures such as security (navy, police, army). The Odo-ogo is a 600-year-old storey building.49It was built to serve as a security tower in the Attah Igala’s palace to monitor the four cardinal points of the palace against enemies. No enemy had ever taken the people of Igala or Idah unawares without being spotted from afar and then prevented. This poem refers to the Odo-ogo tower building and highlights how it was built through the initiative of Attah Abutu Ejeh around the 15th century.50 In the Attah Igala’s palace, the tower had Igala soldiers or warriors at its top while downstairs was used for some special roles in the Attah’s palace (just like the pyramids of ancient Egypt) as a resting place of any Attah who joined his ancestors.

Just like the processes passed through by ancient Egyptian pharaohs in the traditional mortuary (mummification) before burial, a similar process is observed before any transited Attah moves to the other world completely. Till date, this ancient security tower remains a holy ground that people do not go near, except those in charge of it. Today, the ancient Odo-ogo building can be used as one of the literary-culture resources to a historian reconstructing Igala architectural and technological development history, and it is very significant to the historical place of the world. It is preserved for generations to come and can be used for Igala historical reconstruction.51

Onoja Akpa T. is an Igala prose writer from Ejule . One of his numerous prose works titled, OJ! Cravings Of Passion; Reminiscences of Once Upon A Mighty Kingdom, is pregnant and rich. The fictional work received accolades for its literary excellence and has been staged as a drama several times over within and outside Igala kingdom.33 “Inikpi Om’Ayegba Idoko’’ was filmed for viewing by the Nigerian film industry, otherwise known as Nollywood. Between 2018 and 2019, Mercy Johnson produced a play to enrich Igala literature. Igala women were also deeply involved in contributions to the development of Igala literary culture. One of these women, Maryam Seidu Jummai of Ejeh of Ankpa’s family made her mark as an Igala artist in 1989. Although, Mrs. Seidu Jummai was not a prose writer, she enriched Igala literary culture through her artistic works exhibited through industrial design, textiles, painting and sculptures. She sculpted a replica of the leopard in the Ejeh of Ankpa’s Palace, which historically is the symbol of authority of the Ejeh traditional throne in Ankpa. She also sculpted an image of Ogani Angwa Cultural Festival, drumbeaters (anu-koga) and local trumpet (okakachi) the latter of which is mainly used by first class paramount rulers (Attah Igala and Ejeh of Ankpa). These sculptures adorn the outer court of the Ejeh of Ankpa’s palace in Igala kingdom.52

Rev. Fr. Michael A. Umameh also composed a poem about Ubi-Ogba Cliff that expresses much about the natural defence that Ubi-Ogba cliff provides for Igala kingdom. The English version of the poem reads as follows:

UBI-OGBA CLIFFS

Beside the long shadows of malignant trees and

The sweet seasonal stretch of Ohimini (the River Niger)

Fear the steep limestone cliff: Ukwujale (death is right)

Ten thousand feet gathered at Inikpi sacred feet

Sailing and swimming, haggling and selling.

Here royals take tittles politicians tittle-tattle.

There trees speak in green crunchy voices with

The whispering audience of leaves, elephant grass.53

This poem reveals many significant points to a historian that wants to reconstruct Igala history from poems. The poem reveals that there is a legend of Arabic inscription by Attah Ameh Oboni or so on the rock face of ubi-ogba cliff. It commands the River Niger not to rise beyond the mark. Ubi-ogba cliff was a protective shield for the Igala kingdom for many years against regional rivals and helped in the control of the waterways from Lokoja to the Delta. Igala warriors and lookouts were stationed on the cliff. The British Empire bombarded Idah in 1822, 1879, 1882, 1896 and 1900 but could not breach its defenses.54 Thirdly, ubi-ogba cliff offers a very panoramic view of the Niger, Aganabode, Idah, Ala and Ibaji environs as far as the eyes can see.55

Therefore, very significant to the political, socio-cultural and economic survival of the Igala people is the ubi-ogba cliff, the beauty of which the poet describes in this poem. That could serve as a tourist attraction center in Nigeria and the world. Bird-watching is a lucrative pastime and provides a money-spinning opportunity for service providers. These are possibilities and potentials we could explore. Hence, in the words of Joseph Ukwede, the ubi-ogba and River Niger are the main instruments of adornment and blessing to the Igala nation.56

Conclusion

From the foregoing, it could be concluded that between the years 1800 and 2000, Igala literary culture has appreciated to an enviable level, and precisely expresses itself in poetry, prose, publications, plays, music, and songs and other forms of ethnographic data. Aside from being used as a form of entertainment, the aforementioned sources established useful materials that play enviable roles in the reconstruction of Igala history in the Niger-Benue confluence area. Through the sources enumerated above, a historian acquires some knowledge of the social, political, economic and religious views of the Igala society.

Endnotes

- Abdullahi, Musa Yusuf and Ichaba Emmanuel Abiye, “The Rivers Niger and Benue as the Economic Nerve Centre of the Igala Kingdom, Central Nigeria in the Pre-Colonial,” Journal of Research and Developments in Arts and Social Sciences Vol 3, (July, 2018): 191-193.

- Jan Vansina, Oral Tradition: A Study in Historical Methodology (French:1961), and in English, and Oral Tradition as A Source of Reconstruction of People and Their Society History, (1965), 34.

- Jan Vansina, “JSTOR” The Ethnographic Data Account As a Genre in Central Africa, Frobenius Institude:(1900):433-444. www.jstor.org/stable/41409926

- Uya, O.E. Ethnographic Data as Source for the Reconstruction of African History: Some Problems in Methodology and Perspective, (Monograph Series of Cornell University, 1974)

- E.J. Alagoa, Inaugural Lecture Note: The Python Eye: The Past in the Living Present: (University of Porthacourt, 1979), 14.

- Yakubu B.C Omalle, The Igala in The Groundwork of Niger-Benue Confluence History, Z.O. Apata and Yemi Akinwumi (eds), (Ibadan: Cresthill Publishers, 2011), 2.

- Ahmed Rufai Muhammed, History of the Spread of Islam in the Niger-Benue Confluence Area: Igalaland, Ebiraland and Lokoja c.1900-1960 (Ibadan: University Presss, 2014), 1-2.

- Uya, O. E. Ethnographic Data as Sources for the Reconstruction of African History. African History: Some Problems in Methodology and Perspectives. Monograph series of Cornell University, 1974.

- Uya, O. E. Ethnographic Data as Sources for the Reconstruction of African History. African History: Some Problems in Methodology and Perspectives

- Literature and Culture-lanqua.eu www.lanqua.eu>theme>literature-and-…

- Jan Vasina, Oral Tradition as History (United State of America: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985)17, 46.

- E.J. Alagoa, The Python’s Eyes: The Past in the Living Present. An Inaugural Lecture Series No.1, (University of Portharcourt,7 December, 1979).

- James Onalo Ihiabe, Igala People and Their Culture (Akure: Adura Printing/Publishing Press, 2018), 170.

- James Onalo Ihiabe, Igala People and their Culture, 171.

- Michael Achile Umameh, Agwude: Igala Mythical Gladiator (facebook: Poem, published by Michael Achile Umameh, 3 Oct. 2018)

- Michael Achile Umameh, Agwude: Igala Mythical Gladiator

- Ukwede J. N, History of the Igala Kingdom c 1534-1854 (Kaduna: ABU Press, 2003), 211.

- Ukwede J. N, History of the Igala Kingdom c. 1534-1854. 212.

- Michael Achile Umameh, Agwude: Igala mythical Gladiator

- Interview with E.J Alagoa, Age: 87, place; Onyoma Research, no: 11, Orugbom Street, Portharcourt, (2019)

- Michael Achile Umameh, facebook page, seen in Attah Igala Palace Musium, Idah, Kogi State.

- Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart (London: William Heinemann press, 1958), 222.

- Itodo M. Abdulkarim, The Igala Nation and Nigeria’s Sociopolitical Realities: A Sage of Missed Opportunities (Ibadan: University Press, 2019), 128.

- Itodo M. Abdulkarim, The Igala Nation and Nigeria’s Sociopolitical Realities: A Sage of Missed Opportunities.129.

- Victor Alewo Adoji, In one of His Speeches during Kogi East Senatorial District Campaign ( Idah: 17 Novermber, 2019)

- Rev. Fr. Michael Achile Umameh, interpreted the meaning of his Grandfather name via social media messenger (4. September, 2021.)

- James Onalo Ihiabe, Igala People and their Culture, 132.

- Itodo M. Abdulkarim, The Igala Nation and Nigeria’s Sociopolitical Realities: A Sage of Missed Opportunities, (vii)

- Winifred E. Akoda, Efik Literary Culture and its Historical Significance, 1900-1970. (Calabar Journal of Liberal Studies an Interdisciplinary Journal, Vol. Vii No.2 Dec. 2004), 49.

- Uya, O.E. Ethnographic Data as Source for the Reconstruction of African History: Some Problems in Methodology and Perspective, (Monograph Series of Cornell University, 1974), 47.

- Ayegba A. A, The Sixteen Elements of Igala Ifa Ebutu (Sand Ifa) in their Respective Positions or “Houses” (Education and Research Unit, Idah: Igala Kingdom, Kogi State, Sep, 2020), 12.

- Akobe Solomon, Igala: A Nation Now Torn Apart, (a poem, Vol.1) TNV The Nigerian Voice, June 27, 2018.

- Yesufu Etu, Ameh Oboni: His Life, His Reign (Ibadan: Macmillan Publisher, 1989) 26.

- Yesufu Etu, Ameh Oboni: His Life, His Reign

- Yesufu Etu, Ameh Oboni: His Life, His Reign

- John Idakwoji Jibo, An Igala-English Lexicon: A Bilingual Dictionary with Notes on Igala Language. History, Culture and priest-Kings (Singapore: partridge publisher, 2014), 591.

- Odih Daniel Nuhu, Glorious Ane-Igala, facebook, Publication, 2nd August, 2009.

- Ahmed Rufai Muhammed, History of the Spread of Islam in the Niger-Benue Confluence Area: Igalaland, Ebiraland and Lokoja c.1900-1960 (Ibadan: University Presss, 2014),

- P.E. Okwoli, A short History of Igala (Ilorin: Matami and Sons Printing, 1973), 134.

- P.E. Okwoli, A short History of Igala, 135

- P.E. Okwoli, A short History of Igala, 136

- M.O. Adeniyi, Islam in Igala Proverbs, Anyigba Journal of Arts and Humanities. Kogi state University, Nigeria. (December, 2005-2007), 122.

- M.O. Adeniyi, Islam in Igala Proverbs, Anyigba Journal of Arts and Humanities. Kogi state University, Nigeria, 121.

- M.O. Adeniyi, Islam in Igala Proverbs, Anyigba Journal of Arts and Humanities. Kogi state University, Nigeria

- M.O. Adeniyi, Islam in Igala Proverbs, Anyigba Journal of Arts and Humanities. Kogi state University, Nigeria

- Ayegba A. A, The Sixteen Elements of Igala Ifa Ebutu (Sand Ifa) in their Respective Positions or “Houses” (Education and Research Unit, Idah: Igala Kingdom, Kogi State, Sep, 2020), 21.

- John Idakwoji Jibo, An Igala-English Lexicon: A Bilingual Dictionary with Notes on Igala Language. History, Culture and priest-Kings (Singapore: partridge publisher, 2014), 267.

- Edimeh, F. O, The Aj’Ocholi Provenance in Igala History (Ankpa: Roma Prints, 2013), 26.

- Amb. Ayegba A.A, Introduction to Igala Culture and Tourism, (monograph #igala_touristpoint10, 2015),5-7.

- Amb. Ayegba A.A, Introduction to Igala Culture and Tourism, (monograph #igala_touristpoint10, 2015),5-7.

- Amb. Ayegba A.A, Introduction to Igala Culture and Tourism, (monograph #igala_touristpoint10, 2015),5-7.

- Hajiya Maryam Seidu Jummai, Art Works, Ejeh Ankpa’s Palace front view, 1987.

- Rev. Fr. Michael Achile Umameh, Tourism Potential of Ubi-Ogba Cliff (Facebook: published June 10, 2019).

- Rev. Fr. Michael Achile Umameh, Tourism Potential of Ubi-Ogba Cliff (Facebook: published June 10, 2019).

- Rev. Fr. Michael Achile Umameh, Tourism Potential of Ubi-Ogba Cliff (Facebook: published June 10, 2019).

- Ukwede J. N, History of the Igala Kingdom c. 1534-1854. Pp. 311.